Green finance is a special opportunity to make a strategic contribution to achieving European climate targets and preserving our planet. Currently, however, it is still a major challenge for investors and companies, and at the same time raises a number of questions. What is the impact of green finance? How effective are the current requirements? What do investors and companies need to be prepared for now? And: Does Green Finance mean poorer returns?

Green Finance - What is it anyway?

In addition to investing in environmentally friendly and sustainable forms of financing, Green Finance also includes the consideration of environmental and climate protection aspects in the design of the financial system. Green Finance is a sub-area of Sustainable Finance, which takes a holistic view of the three ESG criteria of environment, social affairs and governance.

Although the origins of Green Finance date back to the 1970s, it is only the current increased focus on climate that has led to the key moment. In 2019, the European Commission adopted the Green Deal to implement the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, which aims to make Europe climate neutral by 2050. Investments of around EUR 3.5 trillion will be required. Of this, around EUR 1 trillion will be covered by public funds. The remaining investment gap of at least EUR 2.5 trillion must be covered by the private sector. The basis for this is provided by the EU's Sustainable Finance Framework.

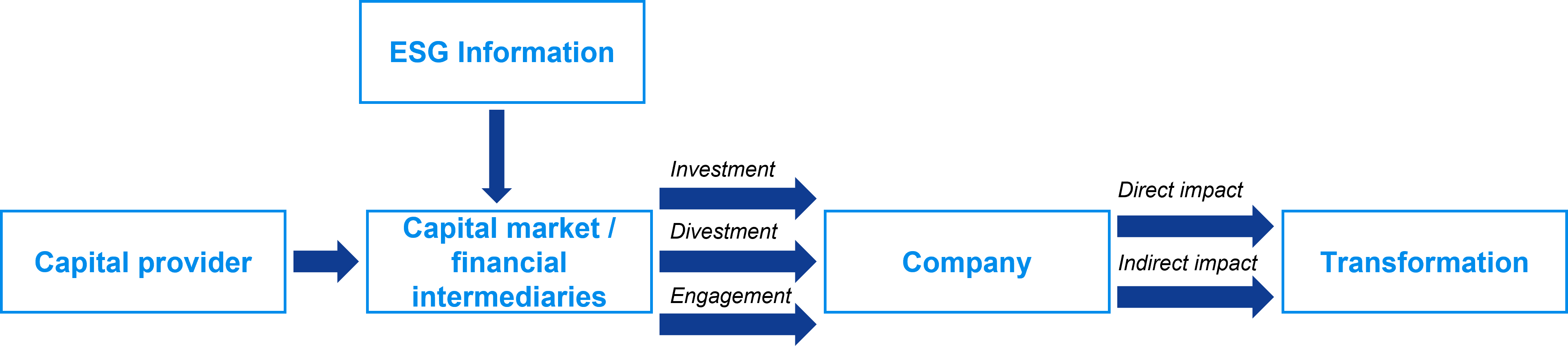

In addition to the sharp increase in regulation, investors are also noticeably increasing the pressure on companies. Many institutional investors, but also private individuals, are consciously opting for sustainable forms of financing - to a certain extent even at the expense of their returns. Green finance increases the investor base, provides more transparency, improves the image and also increases the attractiveness of the company. At the same time, however, the extended requirements in terms of transparency and reporting of green finance products also result in increased costs. Ultimately, therefore, green finance leads to capital being allocated not only according to pure return considerations, but also taking ESG criteria into account (representation based on KfW):

However, the existing regulatory framework is also criticized. Due to the increasing regulatory requirements in the area of sustainability, there is a risk that investments in other future topics such as digitization or cybersecurity will be neglected. Prof. Dr. Dr. h. c. Clemens Fuest and Prof. Dr. Volker Maier of the Ifo Institute also criticize the fact that regulations such as the EU taxonomy can lead to a loss of income within the national economy and to an increase in emissions-intensive production outside the regulated market. Medium-sized companies in particular criticize the enormous resources tied up by the increasing reporting obligations for the necessary data collection and preparation. However, the reporting requirements of ESG regulation are only gradually taking effect for SMEs as well, after the focus is currently still on capital market-oriented companies. However, the increasing pressure from stakeholders such as affiliated companies and customers is already leading to a strong increase in the relevance of green finance for SMEs.

3 R's of green financing: regulation, return, reputation

The derivation of specific areas of action and implementation of concrete actions related to green finance are in the triad of regulation, return and reputation - the 3 R's of green finance. Capital market players and financiers of debt facilities move between these three drivers, which in essence reflect nothing other than:

1. the legislator

2. the profitability = costs

3. the customers = business volume

Financial market players and companies seeking capital basically have to find a balance in this triad if they want to secure their future. Green finance is no different. On the contrary: only now, with the advent of the sustainability goals, has the harmony of the three drivers become even more elementary than before.

To put it somewhat exaggeratedly, investors have so far focused primarily on the primacy of generating returns. Laws provided the framework within which one was allowed to be profitable. Reputation merely had a supporting character to increase or stabilize the business volume, which ultimately also helped the return. Of course, there have always been companies and capital market players for whom reputation and thus the image of the company have always been a high priority.

However, at the latest with the sustainability movement that has emerged in large parts of Western society, a complete recalibration of the priorities and strategic agenda of financial market players and companies has taken place almost overnight.

Regulation has responded to societal pressure and put the onus on financial market players. To this end, it has implemented three elements: First, the EU Taxonomy Regulation provides a generally binding definition of what may be considered a "green" investment - a uniform guideline for everyone. Second, an EU-wide standard for a green financial product has been created via the "EU Green Bonds" in accordance with the EU Taxonomy, which is intended to increase credibility in the product. Third, EU benchmarks ("low-carbon" benchmark) provide uniform reference values for the quality of an investment's sustainability (LBBW Research).

It is a common misconception that sustainability and returns are incompatible. In fact, there are numerous examples of environmentally friendly investments that generate attractive returns. Companies should therefore carefully consider which green finance projects are in their interest and what returns they can expect to remain profitable in the long term. A good reputation for sustainability can support above-average returns. Reputation and returns are more than ever integrated parts of the equation - together with regulation.

Reputation could even become an organization's most important asset. Customers, investors and other stakeholders are increasingly interested in how companies perceive their responsibility towards the environment and act accordingly. It is already evident that a strong reputation in terms of sustainability and environmental protection has a positive impact on the perception of the brand and thus on the value of the company. In addition to popularity with customers and thus sales potential, this also affects the employer brand. Young people starting out in working life in particular are looking for employers with a clear pro-sustainability stance. This is another reason why it is important for companies to actively address the integration of sustainability aspects into their business models and ensure that they invest in environmentally friendly projects.

Green finance has thus become an important factor for companies. It offers them the opportunity to support environmentally friendly projects, helps to enhance both reputation and return on investment, and ensures regulatory compliance. They should look at it carefully to ensure that they are successful in the long term and in a sustainable way.

Regulation as an enabler or the sword of Damocles?

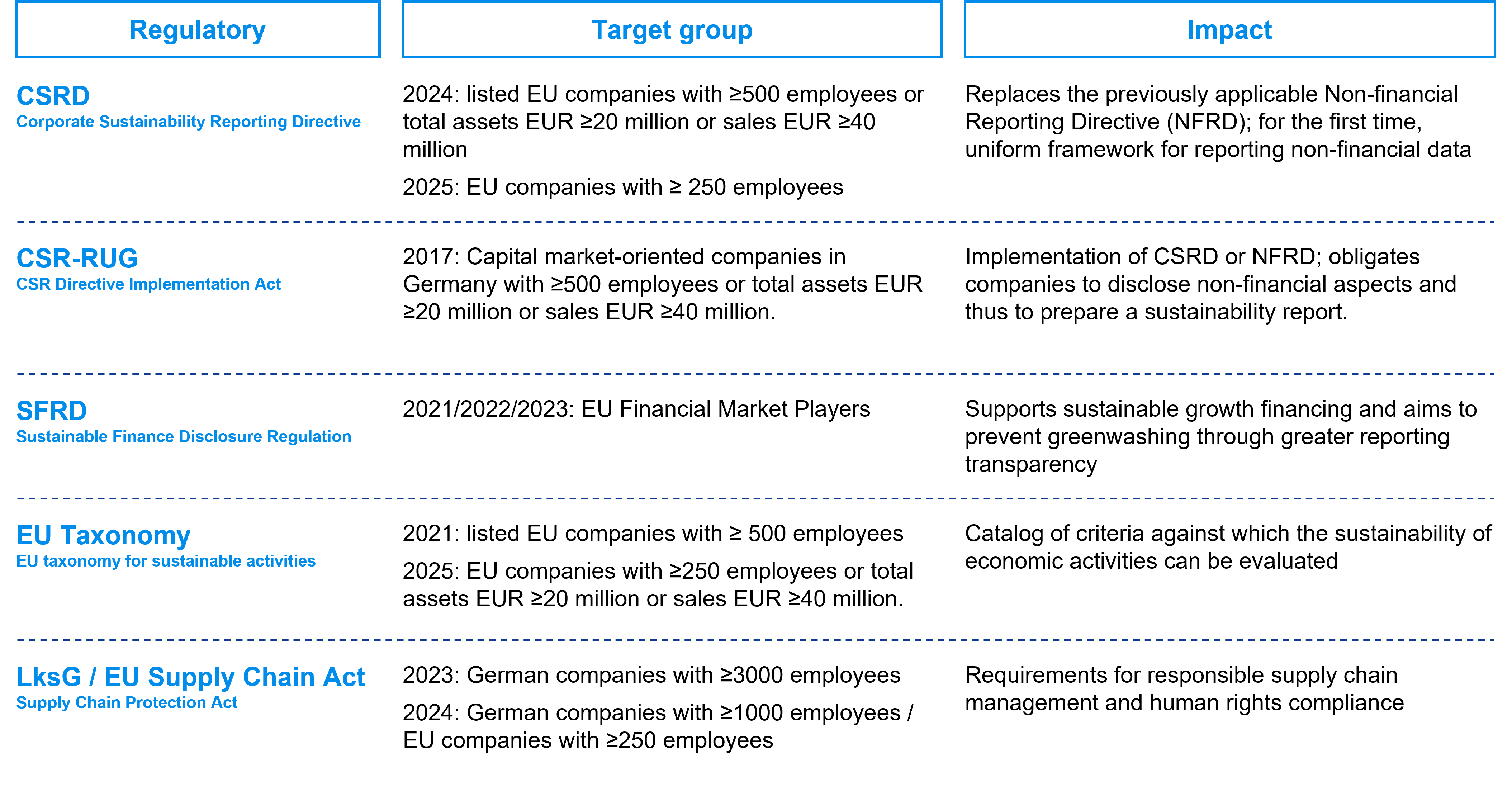

The main driver of ESG regulation in Europe is the EU Green Deal, as a result of which extensive regulatory packages have been adopted at EU level and translated into national law. The most important ESG regulations are the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the CSR Directive Implementation Act (CSR-RUG), the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFRD), the EU Taxonomy, and the Supply Chain Sourcing Obligations Act (LksG) or the EU Supply Chain Act. In addition, work continues on ESG regulation at both the European and national levels. Finding one's way through this almost impenetrable thicket of ESG regulatory specifications and requirements is one of the key challenges for decision-makers in all industries and companies.

In addition, not all regulatory requirements and reporting obligations apply equally to all companies. This makes correct implementation and application on the corporate side even more difficult. The following presentation provides an overview of these regulations, who they apply to, and what goals they pursue:

Small and medium-sized enterprises are an important part of the economy, especially in Germany, and are therefore increasingly being held accountable by the advancing ESG regulations. Compared to large corporations, which have already been subject to CSR reporting since 2017, SMEs are significantly burdened in particular by these reporting obligations anchored in the regulatory framework. In many cases, they lack the resources to take on the additional reporting tasks. In addition, there is a lack of time to deal in detail with the applicable regulations and to collect or prepare the required data. A lack of experience, best practices or templates within the company or in industry or regional associations further complicates implementation.

As a result, the ever stricter regulations on sustainability are often perceived by SMEs as a sword of Damocles and an additional bureaucratic burden. The opportunities that regulatory transparency offers companies are disregarded. For SMEs in particular, regulation offers the opportunity to establish themselves on the financial markets and to score credible points with potential investors there with sustainable products or corporate structures. Especially in volatile economic cycles, this can be a significant competitive advantage when raising capital for sustainable innovations.

Regardless of their size, it is advantageous for all companies to deal with ratified legislation and draft laws at an early stage and to make appropriate arrangements for implementation in their own operations. In principle, the earlier and more structured the implementation projects are tackled, the simpler, less complicated and often also more cost-effective their subsequent application will be.

Over- or underperformer?

The long-term, stable and crisis-proof return on investment usually plays a major role in investment decisions. Historically, it has been shown that trends in particular exert a significant attraction. This in turn carries the risk of hype, for example if investor expectations and valuations develop significantly faster than the trend itself matures.

A current example of this is the topic of hydrogen, which is currently experiencing a renaissance ahead of the move away from Russian oil and gas. Hydrogen shares had achieved significant price gains in 2020, but by the first quarter of 2021 there was not much evidence of this on the stock markets. The price correction occurred after many investors had put money into the trend topic in 2020. In the long-term trend, many hydrogen shares still showed value even after the correction. Only short-term investors were deterred by the slump. In general, the "neo-ecology" megatrend, in the form of the sustainability debate, continues to be a good investment for long-term investors.

Sustainable finance continues to grow rapidly, driven by strong demand from institutional and private investors. In the record year 2021, Bloomberg estimated the global cumulative volume of all ESG assets at just under USD 40 trillion, and forecast it to rise to around USD 53 trillion by 2025. This represents more than one-third of the expected global cumulative investment volume (approximately USD 140 trillion). Debt investments account for a good fifth of the total ESG volume, with a forecast USD 11 trillion. Growth was assumed in a baseline scenario that is significantly lower than the growth observed through 2021. In 2022, we did see a slump in new investment of circa 25% due to the pervasive macroeconomic dislocation in the markets caused by volatility, inflation, interest rate hikes and geopolitical uncertainty. For 2023, however, the level of 2021 is already being targeted, at least for the debt capital markets, which leads us to assume a slight shift in the timing of the above forecasts. Europe is the top dog in sustainable finance. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), around 81% of sustainable funds are based in Europe.

Growth continues to be driven by the development of the debt capital markets. Here, business with sustainable bonds is booming in particular. According to the service provider Refinitiv, sustainable bonds already account for one tenth of the global bond markets. The absolute leaders are green and social bonds, which focus on environmental and social aspects. Bonds issued by companies classified as sustainable have also increased recently.

In terms of returns, there is also statistical evidence to suggest that sustainable investments outperform. For example, a study by asset manager Fidelity shows that more sustainable companies generate significantly higher returns depending on the industry. This is most dramatic in the food and energy industries, where returns are up to 30% higher than the average of peer companies. This is confirmed by a BlackRock study of ESG-rated funds, which shows that funds with a very good ESG rating significantly outperform the index (MSCI USA). A study by Société Générale has also shown that controversial ESG events have a negative long-term impact on a company's share price. In two-thirds of the cases studied, the share price still underperformed the market by an average of 12% in the following two years after the event.

Despite the demonstrably positive performance of ESG investments, there are also concerns about macroeconomic effects due to the focus on sustainable finance. According to the Ifo Institute, if the attractiveness of investments is solely due to government subsidies or regulatory frameworks, there may also be adverse effects on income levels and climate protection. If adverse selection causes less sustainable production to be shifted to less strictly regulated (non-EU) countries, this phenomenon, known as "carbon leakage," means that stricter climate policies in a few economies have a negative global impact on emissions levels. Income leakage occurs when the better return on sustainable investments is based purely on government subsidies, as these are firstly borne by taxpayers and thus at the expense of investors, and secondly there is less incentive to invest in better performing projects or assets.

Reputation becomes the sustainable basis for returns

How does an investor secure an attractive return in terms of sustainability? Due to the regulatory requirements of "Green Finance", investors and financiers are required to make investments in sustainable projects, companies and assets. What was considered a "nice-to-have" just a few years ago has become a strict requirement under the new regulatory regime. Two differences from previous rules will, in our view, make it more effective for financiers to play one, if not the, critical role in addressing our climate goals:

- Reulation responded to public pressure and is thus based on a broad social consensus.

- As a result, financiers and companies can no longer influence their reputation only in a positive sense through sustainable investments or products because, for example, sustainability is their unique selling proposition. From now on, they can also lose reputation if they do not fulfill the regulatory tasks and thus do not comply with the wishes of their stakeholders.

This makes it clear that a positive reputation is the basis for attractive long-term returns. Only companies and thus their investors that build up a positive reputation in terms of sustainability will be successful with their business model in the long term.

A long-term positive reputation is driven by four key aspects:

1. Customers purchase sustainable products

Customers will demand the products of a company that trims production workflows, processes, sales and the products themselves for sustainability in the sense of social conviction and regulation. Meeting sustainability criteria is still seen as a positive feature today. Over time, however, it becomes a hygiene factor. Products that are not considered sustainable are no longer in demand, or only to a very limited extent. The volume of business declines and the company's existence is threatened.

2. More and more job seekers want to work for sustainable companies

Based on a study by StepStone and the Handelsblatt Research Institute, more than 50% of employees fear negative effects on their job satisfaction if their company does not behave sustainably. For three out of four respondents, it is important that sustainability is given high priority by their (potential) employer and thus also has a major influence on its attractiveness. If a non-sustainable company loses the competition for talent, this leads to an immense problem for its continued existence.

3. Penalties for violation of regulatory requirements

Regulators will increasingly impose penalties for non-compliance with regulatory requirements. There are already numerous cases that have become public, such as the green-washing allegations surrounding DWS or the EUR 1 million fine imposed by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) on S&P Global Ratings Europe Limited (S&P) for various breaches of EU regulations. In May 2021, oil company Shell was sued in the Netherlands by several environmental groups and more than 17,000 citizens, alleging violations of global climate targets and financial extraction of oil and natural gas. In May 2022, there were greenwashing allegations and an indictment of securities services provider BNY Mellon by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States. These cases demonstrate very clearly that sustainability has a direct impact on the company's public reputation and returns, as well as its attractiveness on the capital market.

4. Investors seek sustainable investments

Investors, capital providers and lenders will evaluate their investments - whether companies, projects or assets - according to the sustainability impact they have. This impact is additionally strengthened by the characteristics of the first three aspects. A non-sustainable business model poses a major risk in terms of long-term success and the associated return expectations of the investor. In addition, stakeholders increase the pressure on investors to align their portfolio sustainably. In the worst case, they turn away from the investor - due to regulatory requirements or intrinsic conviction.

Conclusion

Investors can already successfully focus on sustainability today without having to sacrifice returns. But the decision to do so should not only be made to be in line with regulatory requirements. They have the capital, the solutions and the expertise to make a difference globally - for a better world. Green Finance is helping to accelerate the process of rethinking and stakeholder demands for greater sustainability. What is clear is that auditing and due diligence are becoming, and have already become, more comprehensive and accurate as a result of the ESG factor. It thus takes more time and cost to find good, sustainable investments. A lack of sustainability, however, is demonstrably punished with discounts on valuations and with a negative reputation. The latter, however, is elementary for a successful business in the long term - also in terms of returns.